OK, Boomer

“OK, Boomer” memes have been everywhere on the internet in recent weeks. The phrase is meant to convey a fundamental disconnect between younger generations and baby boomers. Younger generations, such as Millennials and Gen Z, see baby boomers as clinging to outdated and off-base ideas and this phrase is used to shut down such ideas.

Recently, 25-year-old New Zealand lawmaker, Chloe Swarbrick, hurled the phrase at older colleagues that were heckling her during her speech in support of a climate change bill.

Myrna Blyth, Senior Vice President at AARP attempted a retort, “Okay, millennials, but we’re the people that actually have the money.” Millennials were not pleased with Blyth’s rejoinder and labeled it as “tone deaf.” Jonathan Segal, an employment attorney, attempted more thoughtful response when he tweeted “‘Ok boomer’ is undeniably age-related comment inconsistent with #ADEA. Make clear unacceptable. If employee does not listen, take prompt and proportionate corrective action. #age #HR.” Response to his tweet consisted mostly of “Ok boomer.”

Twitter and other social media platforms have been the main battle ground and posts addressing the”Ok Boomer” debate suggest a widening gap between the young and old. They speak to different attitudes about social and political change and raise questions about how deep the differences go.

For the first time in history, the workforce spans five generations, from the Silent Generation in their 70s and 80s, to Generation Z, those just entering their 20s. This is because people are living, and therefore working, longer than ever before.

Regardless of whether you think “OK Boomer” is funny or hateful, it is clearly an age-related insult, so if you’ve discovered that it’s been said in the workplace, then you need to, at minimum, talk with the employee and let them know that comments like this are inappropriate. Also, make sure to document that you addressed the comment, even if a formal counseling in the situation would be overkill. If the Millennial supervises the Boomer, a comment like “Ok Boomer” should never be made. Further, the comment could become severe or pervasive and, therefore, unlawful age-based harassment if “Ok Boomer” is dropped every time older employees offers comments or make suggestions. It should be against company policy for anybody to make disparaging remarks about age, any age.

Three Circuit Courts Have Ruled: the ADA Does Not Cover Potential Future Disabilities

The Seventh, Eighth and Eleventh Circuits have uniformity refused to extend protections of the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) to employees with a perceived risk of a potential impairment. In each case, an employer either declined to hire an applicant or terminated an employee based on the perceived possibility that the individual, who otherwise did not have an actual disability, would later develop a medical condition that could impair their capacity to perform essential job functions or otherwise pose a safety concern.

Two of the cases involved the same employer, a transportation company that declined to hire a job applicant with a BMI of over 40, and as such, classified as obese. The job at issue was a safety sensitive position because of the perceived risk that the applicant could develop certain medical conditions in the future that could cause sudden incapacitation while working, such as sleep apnea or heart disease. Both the Seventh Circuit and the Eighth Circuit held that obesity alone is not a protected disability under the ADA.

September 2019, the Eleventh Circuit heard a case where an employer terminated a massage therapist who requested time off to travel to Ghana to visit family. The employer stated that they terminated the massage therapist because of the perceived risk that the employee would contract the Ebola virus, due to recent outbreaks of the disease in neighboring countries.

In all three cases, the plaintiffs argued that included in the ADA’s definition of “disability” are situations where an individual is “regarded as” having greater an impairment that substantially limits one or more major life activities. As such, they argued that ADA protections should apply because the employers regarded the individuals as having a risk of developing such an impairment.

The ultimate question in all three cases: does an employer relying upon a potential future disability as the basis for an adverse employment action violate the “regarded as” protections under the ADA? All three circuits concluded that an employee may only pursue a claim under the “regarded as” anti-retaliation provision if the adverse action in question occurred as a result of the employer’s perception of a current, actual disability. The courts found that the statute is intended to encompass only current impairments, not future ones because the language defining “disability” covers individuals “being regarded as having a physical or mental impairment.” Therefore, the courts concluded that an employer cannot discriminate against an applicant or employee based on a perception of potential disability.

It should be noted that the EEOC has argued in one amicus submission that a potential future condition does satisfy the ADA’s “regarded as” definition of “disability” as long as the condition in question otherwise qualifies as a protected disability under the statute. Under the EEOC’s interpretation, an individual’s predisposition to developing a disease because of poverty or other socio-economic circumstances would not be protected by the ADA, however, predisposition to a disease because of a health condition, such as obesity, would be entitled to ADA protections. Stay tuned for developments in this area.

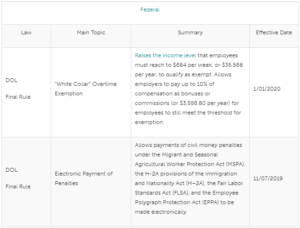

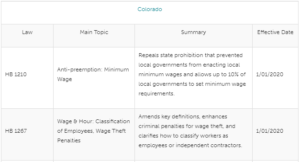

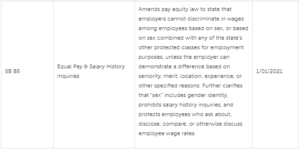

New Laws Taking Effect in the New Year